Illegal immigration from Bangladesh has been a recurring problem for India, but it is now that the volume of illegal immigrants has reached an alarming number. In spite of repeated protests by India, there has been no appreciable sensitivity shown by Bangladesh. India is, of course, cross about this.

The immigrants cross over for two main reasons: economic, and religious oppression of minorities (Hindus) from an Islamic Bangladesh.

Reports suggest that, annually, close to 15 billion dollars are earned by Bangladeshi migrants working and trading in India. Not only does this boost Bangladesh’s GDP, Bangladesh also has less mouths to feed every year. Smuggling is rampant, with cattle and cash and many other items smuggled out of India daily.

Then, there’s the issue of these illegal immigrants acting as cheap labour for various Indian businesses and industries. According to one report, there are over 13 million Bangladeshi labourers working in India… a great many of them in West Bengal (5.4 million), Assam (4 million) and Delhi (1.5 million). This, of course, would not be possible without the help of conspiring local Indian politicians. These local politicians sympathise with these illegal immigrants in order to strengthen their vote banks.

The Indian government, during its successive tenures, has turned a blind eye to this simmering problem, with the result that, now, it’s eating into India’s land, food and water resources, employment opportunities, health and literacy. Above all, it has also become a security threat.

There’s an increase in the crime rate in India and many of the robberies, dacoities and smuggling activities (cash, gold, cattle, arms and body organs) have been traced to Bangladeshi immigrants. There are also traces of subversive and terrorist activities. One report states that, since 1990, Assam has seen the birth of 9 Muslim militant outfits owing allegiance to Harkat ul Mujaheedin and Lashkar-e-Toiba.

According to a recommendation of the National Security System, dating back to February 2001: “The massive illegal immigration poses a grave danger to our security, social harmony and economic well-being. We have compromised on all these aspects so far. It is time to say enough is enough.”

Is anybody listening?

[Citation: South Asia Analysis Group (SAAG)]

31 October 2005

30 October 2005

Cross-border resilience

An editorial from South Asia Forum for Human Rights (SAFHR) points out a cross-border problem close to home. According to the editorial, “India has successfully transformed itself into a national security state… protecting territorial borders with little visible regard for the human lives that inhabit those areas.” The editorial makes a case of the happenings at the Indo-Bangladesh border.

Apparently, the Indian leadership is taking a tough stand on illegal immigrants. Unfortunately, very few people living in the border region between India and Bangladesh have a citizenship of either country, possessing the proper legal papers to prove who they are. These people are caught between the forces of both countries, with no place to go. They feel policing by both countries as prejudiced and discriminatory.

At times, there are serious outbursts of violence, increasing ethnic, social and political tensions between the two countries. But, the migration just can’t be stopped. Scarcity of land and water, natural disasters, unemployment, degrading living conditions in the less-developed Bangladesh automatically induce migration into India. India feels this destabilizes it socio-political, economic and ethnic position, and is willing to do whatever is necessary to stop or, at least, reduce the flow of migration.

The editorial is rather silent on Bangladesh. However, it presents a case for India’s wrongful attitude to cross-border migration through the Indo-Bangladesh border, tracing its history from 1947 to present-day, commenting on how the border is consistently being militarized. It blames India’s Border Security Force (BSF) for its merciless treatment of the immigrants, killing many, sparing no one, branding its victims as infiltrators, ISI agents and smugglers.

Still, India finds its cross-border migration a tough issue to handle. The immigrants are resilient and will stop at nothing. As the report says, “Threatened and hungry people will defy borders whether by braving bullets or by melting into the darkness.”

Apparently, the Indian leadership is taking a tough stand on illegal immigrants. Unfortunately, very few people living in the border region between India and Bangladesh have a citizenship of either country, possessing the proper legal papers to prove who they are. These people are caught between the forces of both countries, with no place to go. They feel policing by both countries as prejudiced and discriminatory.

At times, there are serious outbursts of violence, increasing ethnic, social and political tensions between the two countries. But, the migration just can’t be stopped. Scarcity of land and water, natural disasters, unemployment, degrading living conditions in the less-developed Bangladesh automatically induce migration into India. India feels this destabilizes it socio-political, economic and ethnic position, and is willing to do whatever is necessary to stop or, at least, reduce the flow of migration.

The editorial is rather silent on Bangladesh. However, it presents a case for India’s wrongful attitude to cross-border migration through the Indo-Bangladesh border, tracing its history from 1947 to present-day, commenting on how the border is consistently being militarized. It blames India’s Border Security Force (BSF) for its merciless treatment of the immigrants, killing many, sparing no one, branding its victims as infiltrators, ISI agents and smugglers.

Still, India finds its cross-border migration a tough issue to handle. The immigrants are resilient and will stop at nothing. As the report says, “Threatened and hungry people will defy borders whether by braving bullets or by melting into the darkness.”

28 October 2005

The future of (international) migration

"The primary reason there is not more migration is that the citizens of the industrialized world don’t want it."

[Lant Pritchett, economist]

Let’s face it, international migration takes place because people from poor nations move to the rich industrialised nations. Considering the number of poor nations in the world – and the billions of people who suffer there – by now, we ought to have seen international migration in larger numbers. Then, why don’t we?

According to one school of thought, that’s because forces of mass migration face opposition – in, at least, three different ways. Some people in industrialised nations believe that their own poor will suffer if they allowed in immigrants as cheap labour. Some others believe that trade in goods is sufficient to create a convergence of incomes worldwide. Even others believe that sending enough aid to poor countries will forestall increasing migration.

Is there any evidence to support this? Economist Lant Pritchett is not so sure. He believes, sooner or later, politicians and heads of states will take steps to develop a domestic and international migration regime. The idea behind it being prevention – or, at least, stemming – of population migration. How will this work? I don’t know yet, but it is likely that the anti-migration sentiments of the rich ‘receiving’ countries will play an important part in stemming the population influx.

In a November 2003 article titled, The Future of Migration, a 2-part series from YaleGlobal, Pritchett writes, "Technically, migration is prevented by people with guns. It is the threat of violence that prevents people from crossing borders to take advantage of the economic opportunities. In nearly all industrialized countries (the preferred destinations of migrants) the people with guns are employed by a democratic government, a government which usually represents the preferences of its citizens. Thus, the primary reason there is not more migration is that the citizens of the industrialized world don’t want it."

Pritchett goes on to dispel several myths about migration increase and control, including those beliefs cited earlier in this post, holding his fort with fairly sound reasoning. Of course, he states, the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) have their tasks cut out as well: to halve poverty, ensure universal completion of primary schooling, and reduce infant mortality by two-thirds before 2015. The question is, will the MDGs be achieved in every country? And, what if they aren’t?

Once again, Lant Pritchett comes up with a proposition. But don’t take my word for it; read his article on The Future of Migration and find out.

[Lant Pritchett, economist]

Let’s face it, international migration takes place because people from poor nations move to the rich industrialised nations. Considering the number of poor nations in the world – and the billions of people who suffer there – by now, we ought to have seen international migration in larger numbers. Then, why don’t we?

According to one school of thought, that’s because forces of mass migration face opposition – in, at least, three different ways. Some people in industrialised nations believe that their own poor will suffer if they allowed in immigrants as cheap labour. Some others believe that trade in goods is sufficient to create a convergence of incomes worldwide. Even others believe that sending enough aid to poor countries will forestall increasing migration.

Is there any evidence to support this? Economist Lant Pritchett is not so sure. He believes, sooner or later, politicians and heads of states will take steps to develop a domestic and international migration regime. The idea behind it being prevention – or, at least, stemming – of population migration. How will this work? I don’t know yet, but it is likely that the anti-migration sentiments of the rich ‘receiving’ countries will play an important part in stemming the population influx.

In a November 2003 article titled, The Future of Migration, a 2-part series from YaleGlobal, Pritchett writes, "Technically, migration is prevented by people with guns. It is the threat of violence that prevents people from crossing borders to take advantage of the economic opportunities. In nearly all industrialized countries (the preferred destinations of migrants) the people with guns are employed by a democratic government, a government which usually represents the preferences of its citizens. Thus, the primary reason there is not more migration is that the citizens of the industrialized world don’t want it."

Pritchett goes on to dispel several myths about migration increase and control, including those beliefs cited earlier in this post, holding his fort with fairly sound reasoning. Of course, he states, the Millenium Development Goals (MDGs) have their tasks cut out as well: to halve poverty, ensure universal completion of primary schooling, and reduce infant mortality by two-thirds before 2015. The question is, will the MDGs be achieved in every country? And, what if they aren’t?

Once again, Lant Pritchett comes up with a proposition. But don’t take my word for it; read his article on The Future of Migration and find out.

25 October 2005

Breaking down the barriers

Human migration is at an all-time high in terms of absolute numbers. More people have moved from their home territories to new areas in the past 5 years than ever before. According to Gaia Watch of the UK, at the start of the 21st century, one out of every 35 persons worldwide was an international migrant. In 2002, almost one in every 10 persons living in the more developed regions of the world was a migrant. In the 1990–2000 period, the more developed regions were gaining about 2.6 million persons annually through net international migration and this migration was accounting for two thirds of the population growth in these regions.

Not only has there been cross-border or international migration, even within countries, people have moved from rural areas into towns and cities. Recent population figures indicate that the urban population of the world is continuing to grow faster than the total world population. In 2003, about 48 per cent of the world population lived in urban settlements. Economists say, this was foreseen and is really a by-product of rapid urbanisation. With globalisation, the growth of urban industries and lack of employment in the agricultural sector, cities promise prosperity to millions of people across the world. Of course, this is prevalent in Asian and African nations, but migration figures also support Latin American nations and Eastern Europe.

People migrate for various reasons. Most people move for economic reasons, but some migrate to escape political or religious persecution… or simply to fulfil a personal dream. Widespread unemployment, lack of farmland for agriculture or business opportunities, natural calamities, or war at home are some clear reasons for migration. Encouraging these are factors that attract migrants to another country or a city: a thriving economy, a labour shortage, and favourable immigration laws where international migration is concerned. However, there’s no denying that the greatest attraction lies in the promise of wealth and better living standards.

Perhaps this problem is yet to spark a political or religious war, but it certainly is breaking down some of the economic barriers.

[Citation: Gaia Watch of the UK, Population Research Bureau.]

Not only has there been cross-border or international migration, even within countries, people have moved from rural areas into towns and cities. Recent population figures indicate that the urban population of the world is continuing to grow faster than the total world population. In 2003, about 48 per cent of the world population lived in urban settlements. Economists say, this was foreseen and is really a by-product of rapid urbanisation. With globalisation, the growth of urban industries and lack of employment in the agricultural sector, cities promise prosperity to millions of people across the world. Of course, this is prevalent in Asian and African nations, but migration figures also support Latin American nations and Eastern Europe.

People migrate for various reasons. Most people move for economic reasons, but some migrate to escape political or religious persecution… or simply to fulfil a personal dream. Widespread unemployment, lack of farmland for agriculture or business opportunities, natural calamities, or war at home are some clear reasons for migration. Encouraging these are factors that attract migrants to another country or a city: a thriving economy, a labour shortage, and favourable immigration laws where international migration is concerned. However, there’s no denying that the greatest attraction lies in the promise of wealth and better living standards.

Perhaps this problem is yet to spark a political or religious war, but it certainly is breaking down some of the economic barriers.

[Citation: Gaia Watch of the UK, Population Research Bureau.]

24 October 2005

Doubling time

The World Population Awareness Week (17-23 October) just got over. I bet you didn’t even know. You didn’t even know that such a thing as a World Population Awareness Week exists. After all, nothing much was reported in the media. Nothing much was talked about in other circles either. Where are all those social activists who rave and rant about world population growth?

No matter, let me clear the air a bit. The World Population Awareness Week doesn’t directly deal with issues such as overpopulation or population growth. It focuses on gender inequalities… about the inequalities women face in healthcare, education, employment… about the importance of family planning. After all, the decision to have children is the very essence of freedom.

Attached to this very issue is the matter of human birth and population… the matter of population growth and distribution. If you’ve followed my posts over the last couple of days, you would have read about the concern many sociologists, economists, politicians and heads of states have about the growing population in the world. To put it crudely, there are too many people in this world… and they are multiplying rapidly.

Population grows geometrically (1, 2, 4, 8…), rather than arithmetically (1, 2, 3, 4…), which is why the numbers can increase so quickly.

"A story said to have originated in Persia offers a classic example of exponential growth. It tells of a clever courtier who presented a beautiful chess set to his king and in return asked only that the king give him one grain of rice for the first square, two grains, or double the amount, for the second square, four grains (or double again) for the third, and so forth. The king, not being mathematically inclined, agreed and ordered the rice to be brought from storage. The eighth square required 128 grains, the 12th took more than one pound. Long before reaching the 64th square, every grain of rice in the kingdom had been used. Even today, the total world rice production would not be enough to meet the amount required for the final square of the chessboard. The secret to understanding the arithmetic is that the rate of growth (doubling for each square) applies to an ever-expanding amount of rice, so the number of grains added with each doubling goes up, even though the rate of growth is constant."

Similarly, for population. It works on the principle of doubling time. Doubling time refers to the number of years required for the population of an area to double its present size, given the current rate of population growth. Population doubling time is useful to demonstrate the long-term effect of a growth rate, but should not be used to project population size of a specific area… as several other factors can influence population growth.

[Citation: Population Reference Bureau, Population Growth]

No matter, let me clear the air a bit. The World Population Awareness Week doesn’t directly deal with issues such as overpopulation or population growth. It focuses on gender inequalities… about the inequalities women face in healthcare, education, employment… about the importance of family planning. After all, the decision to have children is the very essence of freedom.

Attached to this very issue is the matter of human birth and population… the matter of population growth and distribution. If you’ve followed my posts over the last couple of days, you would have read about the concern many sociologists, economists, politicians and heads of states have about the growing population in the world. To put it crudely, there are too many people in this world… and they are multiplying rapidly.

Population grows geometrically (1, 2, 4, 8…), rather than arithmetically (1, 2, 3, 4…), which is why the numbers can increase so quickly.

"A story said to have originated in Persia offers a classic example of exponential growth. It tells of a clever courtier who presented a beautiful chess set to his king and in return asked only that the king give him one grain of rice for the first square, two grains, or double the amount, for the second square, four grains (or double again) for the third, and so forth. The king, not being mathematically inclined, agreed and ordered the rice to be brought from storage. The eighth square required 128 grains, the 12th took more than one pound. Long before reaching the 64th square, every grain of rice in the kingdom had been used. Even today, the total world rice production would not be enough to meet the amount required for the final square of the chessboard. The secret to understanding the arithmetic is that the rate of growth (doubling for each square) applies to an ever-expanding amount of rice, so the number of grains added with each doubling goes up, even though the rate of growth is constant."

Similarly, for population. It works on the principle of doubling time. Doubling time refers to the number of years required for the population of an area to double its present size, given the current rate of population growth. Population doubling time is useful to demonstrate the long-term effect of a growth rate, but should not be used to project population size of a specific area… as several other factors can influence population growth.

[Citation: Population Reference Bureau, Population Growth]

22 October 2005

The Population Bomb

“Just remember that, at the current growth rate, in a few thousand years everything in the visible universe would be converted into people, and the ball of people would be expanding at the speed of light.”

[Paul Ehrlich, The Population Bomb]

In the early 1970s (perhaps late 1960s, I’m not quite sure), Paul Ehrlich in his (now infamous) book, The Population Bomb, predicted that, by the end of the 20th century, human want would outstrip available resources; India would collapse due to its inability to feed itself; and mass starvation would sweep the globe. Many believed him then, accepting his words as some sort of prophecy. However, as you can see, you are all still here reading this blog; and Ehrlich’s dark words now sound like the words of a madman… or, at least, pure fantasy.

Ehrlich believed that our planet’s natural resources were finite and would, one day, be used up if our demand for them did not decrease. With an ever-increasing population fuelling demand and rapid industrialization consuming more and more resources, he felt confident of his prediction. Added to this were his concerns over pollution, environmental degradations and incidence of widespread diseases. Today, although we are alive and have not disintegrated into an Ehrlich-style catastrophe, we do carry concerns over the same issues.

The growth in world population is indeed a problem in our hands… spurring on related concerns over food, water, healthcare, housing, electricity, education, employment… and depletion of natural resources such as forests and oil reserves. But, that’s not all that’s bothering us today. Migrations of huge numbers of people from less developed countries to developed nations, and from rural areas into cities within a country have become socio-economic as well as political problems.

According to the Population Reference Bureau, an US Agency researching population trends and their implications:

“Through most of history, the human population has lived a rural lifestyle, dependent on agriculture and hunting for survival. In 1800, only 3 percent of the world's population lived in urban areas. By 1900, almost 14 percent were urbanites, although only 12 cities had 1 million or more inhabitants. In 1950, 30 percent of the world's population resided in urban centers. The number of cities with over 1 million people had grown to 83.

The world has experienced unprecedented urban growth in recent decades. In 2000, about 47 percent of the world's population lived in urban areas, about 2.8 billion. There are 411 cities over 1 million. More developed nations are about 76 percent urban, while 40 percent of residents of less developed countries live in urban areas. However, urbanization is occurring rapidly in many less developed countries. It is expected that 60 percent of the world population will be urban by 2030, and that most urban growth will occur in less developed countries.”

[Paul Ehrlich, The Population Bomb]

In the early 1970s (perhaps late 1960s, I’m not quite sure), Paul Ehrlich in his (now infamous) book, The Population Bomb, predicted that, by the end of the 20th century, human want would outstrip available resources; India would collapse due to its inability to feed itself; and mass starvation would sweep the globe. Many believed him then, accepting his words as some sort of prophecy. However, as you can see, you are all still here reading this blog; and Ehrlich’s dark words now sound like the words of a madman… or, at least, pure fantasy.

Ehrlich believed that our planet’s natural resources were finite and would, one day, be used up if our demand for them did not decrease. With an ever-increasing population fuelling demand and rapid industrialization consuming more and more resources, he felt confident of his prediction. Added to this were his concerns over pollution, environmental degradations and incidence of widespread diseases. Today, although we are alive and have not disintegrated into an Ehrlich-style catastrophe, we do carry concerns over the same issues.

The growth in world population is indeed a problem in our hands… spurring on related concerns over food, water, healthcare, housing, electricity, education, employment… and depletion of natural resources such as forests and oil reserves. But, that’s not all that’s bothering us today. Migrations of huge numbers of people from less developed countries to developed nations, and from rural areas into cities within a country have become socio-economic as well as political problems.

According to the Population Reference Bureau, an US Agency researching population trends and their implications:

“Through most of history, the human population has lived a rural lifestyle, dependent on agriculture and hunting for survival. In 1800, only 3 percent of the world's population lived in urban areas. By 1900, almost 14 percent were urbanites, although only 12 cities had 1 million or more inhabitants. In 1950, 30 percent of the world's population resided in urban centers. The number of cities with over 1 million people had grown to 83.

The world has experienced unprecedented urban growth in recent decades. In 2000, about 47 percent of the world's population lived in urban areas, about 2.8 billion. There are 411 cities over 1 million. More developed nations are about 76 percent urban, while 40 percent of residents of less developed countries live in urban areas. However, urbanization is occurring rapidly in many less developed countries. It is expected that 60 percent of the world population will be urban by 2030, and that most urban growth will occur in less developed countries.”

21 October 2005

City of Crows

The demands of rising population are many, and Bombay faces its frenzy almost everyday. More and more people are joining the city’s already overcrowded streets, pushing the limits of socio-demographic parameters and throwing the city’s governing council into deeper trouble. But what can they do? At one level, it means providing housing, water, electricity, sanitation, healthcare and education for millions. At another, it’s a huge vote bank to rely upon during elections.

But, what about those millions who enter the city with hope? How are their lives affected by this migration… this force-fit situation? Some Bombay residents argue: How does it matter to them? It’s us who suffer from this invasion… this encroachment into our lives and our livelihoods. These immigrants come in and take away our jobs, our businesses and our incomes, robbing us of our own possessions. Some simply watch and accept this as life… or existence, leaving it to the government to deal with it.

Whatever be the argument, there’s no denying that this migration of people into Bombay is an old phenomenon. For years, people from various parts of the country have landed up in Bombay… nurturing their personal hopes and ambitions. What’s become of them? What are their stories? If you’d like to know, then there’s no better example than tracing Bombay’s own Dharavi slum to understand their predicament.

A great deal has been written about Dharavi and its problems, but I can introduce you to one that has captured my attention and has remained with me for sometime. It’s a photo-essay by Robert Appleby and is available in two parts: a story called City of Crows and a photo album that accompanies it. It’s not just representative of Dharavi, but Bombay as well… although from a foreigner’s point of view.

But, what about those millions who enter the city with hope? How are their lives affected by this migration… this force-fit situation? Some Bombay residents argue: How does it matter to them? It’s us who suffer from this invasion… this encroachment into our lives and our livelihoods. These immigrants come in and take away our jobs, our businesses and our incomes, robbing us of our own possessions. Some simply watch and accept this as life… or existence, leaving it to the government to deal with it.

Whatever be the argument, there’s no denying that this migration of people into Bombay is an old phenomenon. For years, people from various parts of the country have landed up in Bombay… nurturing their personal hopes and ambitions. What’s become of them? What are their stories? If you’d like to know, then there’s no better example than tracing Bombay’s own Dharavi slum to understand their predicament.

A great deal has been written about Dharavi and its problems, but I can introduce you to one that has captured my attention and has remained with me for sometime. It’s a photo-essay by Robert Appleby and is available in two parts: a story called City of Crows and a photo album that accompanies it. It’s not just representative of Dharavi, but Bombay as well… although from a foreigner’s point of view.

20 October 2005

Homeless in Bombay

Like millions of others, I came to Bombay to find a place I could call my home. I wanted to work hard, make money, settle down. Unlike millions of others, I got lucky – to an extent. Work hard I did. Made money too – not a lot perhaps, but some. But, one thing I haven't done yet is settle down.

That’s because I still haven’t got used to Bombay’s dense overpopulated claustrophobic life, its disorderly growth, its noisy garbage-filled streets, and its dirty rundown slums that occupy at least half the city. Did you know that, of the 18 million people living in Bombay today, two-thirds live in slums or on the streets?

What happens to these people everyday when I’m too busy with my work or my social life… or sleeping cozily in my bed at night? Do I even care about them?

In a heart-warming story, Bombay: Turmoil and a Heart-Shaped Balloon, on www.thingsasian.com Kenneth Champeon presented a 360-degree sort of view that had me thinking for several days. It went something like this:

“The Bombay homeless are not easily ignored. They sleep at doorsteps… crevices of unopened shops… Girls slept on the medians of thoroughfares; their mothers rocked cradles made from two sticks and a taut cloth.

The unchecked growth in population is a grave concern. One Indian colleague of mine cited it as the source of all of India's problems… Recent estimates of Bombay's population density reach the incomprehensible figure of 17,676 per square kilometer, compared to 1,200 of London (Seabrook, 49). The Times of India regularly reported transport vehicles backing or barreling over a lone child, or rows of sleeping citizens. Taxis plowed into tea-couriers, cows.”

According to a BBC News article, Bombay faces population boom, Bombay’s population will reach 28.5 million by the year 2020, and Bombay will replace Tokyo as the most populated city in the world.

Do I even care about what will happen then?

That’s because I still haven’t got used to Bombay’s dense overpopulated claustrophobic life, its disorderly growth, its noisy garbage-filled streets, and its dirty rundown slums that occupy at least half the city. Did you know that, of the 18 million people living in Bombay today, two-thirds live in slums or on the streets?

What happens to these people everyday when I’m too busy with my work or my social life… or sleeping cozily in my bed at night? Do I even care about them?

In a heart-warming story, Bombay: Turmoil and a Heart-Shaped Balloon, on www.thingsasian.com Kenneth Champeon presented a 360-degree sort of view that had me thinking for several days. It went something like this:

“The Bombay homeless are not easily ignored. They sleep at doorsteps… crevices of unopened shops… Girls slept on the medians of thoroughfares; their mothers rocked cradles made from two sticks and a taut cloth.

The unchecked growth in population is a grave concern. One Indian colleague of mine cited it as the source of all of India's problems… Recent estimates of Bombay's population density reach the incomprehensible figure of 17,676 per square kilometer, compared to 1,200 of London (Seabrook, 49). The Times of India regularly reported transport vehicles backing or barreling over a lone child, or rows of sleeping citizens. Taxis plowed into tea-couriers, cows.”

According to a BBC News article, Bombay faces population boom, Bombay’s population will reach 28.5 million by the year 2020, and Bombay will replace Tokyo as the most populated city in the world.

Do I even care about what will happen then?

19 October 2005

Bombay streets

Photographing Bombay streets can be quite a feat. The streets are overcrowded and there’s always a problem of finding a safe place to stand to a take a shot. Whenever I’ve found a safe spot, moving people and traffic have come in the way of my shot... so much so that taking the shot has always been a split-second decision for me.

Then, there’s the choice of subject and framing. Half the city looks like a slum, with shacks, sewage and waste dumps making up the landscape. Buildings are badly maintained. Walls are defiled with dirt and posters. Footpaths are taken up by hawkers selling their wares, beggars with deformities, people sleeping in corners or below lampposts; all are badly littered and stained.

On most occasions, I’m not sure what to photograph, as most scenes look similarly ungainly. Hence, I stick to photographing buildings.

This photoblog from "m" is representative of my views.

Then, there’s the choice of subject and framing. Half the city looks like a slum, with shacks, sewage and waste dumps making up the landscape. Buildings are badly maintained. Walls are defiled with dirt and posters. Footpaths are taken up by hawkers selling their wares, beggars with deformities, people sleeping in corners or below lampposts; all are badly littered and stained.

On most occasions, I’m not sure what to photograph, as most scenes look similarly ungainly. Hence, I stick to photographing buildings.

This photoblog from "m" is representative of my views.

17 October 2005

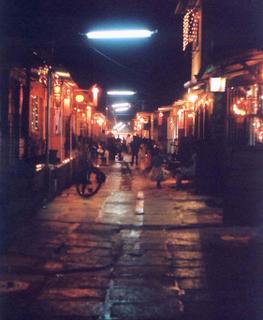

Bombay from the streets

There's more to street photography in India than meets the eye (at least, as far as the above picture goes). But, professional street photographers are difficult to find... anywhere in the world. The profession doesn't pay much. And, few understand its abstraction and beauty.

My photograph of a Diwali Celebration in a Chawl (ghetto) is a sample of what street photography can be and, hence, I've posted it here. However, I have a great deal to learn about street photography... and am doing so by reading on the Net. In fact, Wikipedia has an informative, though clinical, article on the subject which I've just discovered.

You can also read another recent account by Colin and Christian Jago from Scotland at auspiciousdragon.net. Of course, the best learning takes place shooting pictures on the streets.

16 October 2005

Street photography 2

What exactly is street photography?

It’s photography on the streets, or anywhere else for that matter. What highlights street photography is a freedom – a non-existence of rules – that the photographer has in choosing, composing and shooting his subjects. The photographer is not bound by any special equipment, accessories or technicalities of photography… and is free to move around (thanks to the lack of equipment) and shoot whatever he or she feels like.

People are common subjects for street photographers. So are activities and events, or a lack of them, which reflect different moods on the streets. No street photo is less artistic or less scientific than another. Spontaneity is key in capturing a good street shot. Which means, street photography is self-expression in its truest sense. It’s about the photographer, not the subject.

Does street photography follow any guidelines at all?

Really speaking, three things matter in street photography: enthusiasm, an open mind, and creativity – most of which cannot be taught. Of course, you do need a camera with film in it. A digital camera is perhaps lighter and easier to carry. And, it helps to keep your subjects in focus; although, I’ve seen many blurred and out-of-focus shots which are excellent examples of street photography. In fact, street photographers usually take advantage of available light (including soft light and shadows), weather (rain and fog can act as low-budget special-effects), and movement.

That’s enough from me. It’s time to see some good street photography, and these links are simply great: iN-PUBLiC, Alan Wilson, Johnny Mobasher, ZoneZero.

If you’d like to get a clearer perspective on what I’ve said so far on street photography, then visit http://www.nonphotography.com and you'll get the picture.

It’s photography on the streets, or anywhere else for that matter. What highlights street photography is a freedom – a non-existence of rules – that the photographer has in choosing, composing and shooting his subjects. The photographer is not bound by any special equipment, accessories or technicalities of photography… and is free to move around (thanks to the lack of equipment) and shoot whatever he or she feels like.

People are common subjects for street photographers. So are activities and events, or a lack of them, which reflect different moods on the streets. No street photo is less artistic or less scientific than another. Spontaneity is key in capturing a good street shot. Which means, street photography is self-expression in its truest sense. It’s about the photographer, not the subject.

Does street photography follow any guidelines at all?

Really speaking, three things matter in street photography: enthusiasm, an open mind, and creativity – most of which cannot be taught. Of course, you do need a camera with film in it. A digital camera is perhaps lighter and easier to carry. And, it helps to keep your subjects in focus; although, I’ve seen many blurred and out-of-focus shots which are excellent examples of street photography. In fact, street photographers usually take advantage of available light (including soft light and shadows), weather (rain and fog can act as low-budget special-effects), and movement.

That’s enough from me. It’s time to see some good street photography, and these links are simply great: iN-PUBLiC, Alan Wilson, Johnny Mobasher, ZoneZero.

If you’d like to get a clearer perspective on what I’ve said so far on street photography, then visit http://www.nonphotography.com and you'll get the picture.

15 October 2005

Street photography 1

When I was younger and had time to spare – like on a weekend – I’d pick up my camera and just head out on the streets, taking photos of whatever caught my fancy. I’d shoot buildings (I have a fascination for old architecture), hoardings with interesting messages, trees and people.

Of all my subjects, people were the most difficult to photograph, and I was always afraid of photographing them. They hardly ever remained stationary long enough for me to get them in the frame and click the shutter. And, even if they didn’t move too much, by the time I’d get close enough to get a good shot, they’d get up and walk away. So much was my disappointment at this that I had decided to give up street photography altogether.

In fact, I didn’t even know that my sojourn on the streets with my camera was considered a genre of photography called ‘street photography’. Then, a couple of days ago, I read an article called ‘The Indecisive Moment’ by Gerry Badger on ‘stream-of-consciousness’ photography, from Issue 9 of the Harvard journal ‘Fantastic’. And, while reading about Robert Frank, William Klein and Garry Winogrand, my passion for street photography was re-kindled.

From an article on Garry Winogrand by Peter Marshall from the portal About.com, I discovered that (and I quote from the article):

“Winogrand was the photographer who more or less invented and defined the genre we know as ‘street photography’; from his first photography until his death he photographed mainly on the streets – and his best work is on the streets of New York. Of course others had photographed on the street before, in particular Europeans such as [Andre] Kertesz and many of the New York photographers associated with the Photo League, but their work was largely concerned with character and anecdote; with Winogrand the view was wider and could be considered environmental. He photographed people, but his focus was on the street and the person (or people) in it rather than simply on the person.”

But, what really moved me was a quote from Winogrand, reproduced at the end of the Harvard ‘Fantastic’ article by Gerry Badger:

“I look at the pictures I have done up to now, and they make me feel that who we are and what is to become of us just doesn’t matter. Our aspirations and successes have been cheap and petty. I read the newspapers, the columnists, some books. I look at the magazines (our press). They all deal in illusions and fantasies. I can only conclude that we have lost ourselves, and that the bomb may finish the job permanently, and it just doesn’t matter, we have not loved life.”

[Garry Winogrand, quoted in John Szarkowski, Winogrand: Figments from the Real World, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1988, p 34.]

You can see Garry Winogrand’s pioneering work here.

Of all my subjects, people were the most difficult to photograph, and I was always afraid of photographing them. They hardly ever remained stationary long enough for me to get them in the frame and click the shutter. And, even if they didn’t move too much, by the time I’d get close enough to get a good shot, they’d get up and walk away. So much was my disappointment at this that I had decided to give up street photography altogether.

In fact, I didn’t even know that my sojourn on the streets with my camera was considered a genre of photography called ‘street photography’. Then, a couple of days ago, I read an article called ‘The Indecisive Moment’ by Gerry Badger on ‘stream-of-consciousness’ photography, from Issue 9 of the Harvard journal ‘Fantastic’. And, while reading about Robert Frank, William Klein and Garry Winogrand, my passion for street photography was re-kindled.

From an article on Garry Winogrand by Peter Marshall from the portal About.com, I discovered that (and I quote from the article):

“Winogrand was the photographer who more or less invented and defined the genre we know as ‘street photography’; from his first photography until his death he photographed mainly on the streets – and his best work is on the streets of New York. Of course others had photographed on the street before, in particular Europeans such as [Andre] Kertesz and many of the New York photographers associated with the Photo League, but their work was largely concerned with character and anecdote; with Winogrand the view was wider and could be considered environmental. He photographed people, but his focus was on the street and the person (or people) in it rather than simply on the person.”

But, what really moved me was a quote from Winogrand, reproduced at the end of the Harvard ‘Fantastic’ article by Gerry Badger:

“I look at the pictures I have done up to now, and they make me feel that who we are and what is to become of us just doesn’t matter. Our aspirations and successes have been cheap and petty. I read the newspapers, the columnists, some books. I look at the magazines (our press). They all deal in illusions and fantasies. I can only conclude that we have lost ourselves, and that the bomb may finish the job permanently, and it just doesn’t matter, we have not loved life.”

[Garry Winogrand, quoted in John Szarkowski, Winogrand: Figments from the Real World, Museum of Modern Art, New York, 1988, p 34.]

You can see Garry Winogrand’s pioneering work here.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)